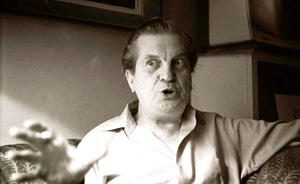

For the past six years I’ve been working on a biography of Canadian War Artist and designer Eric Aldwinckle. Around 1976, my high school friend Timothy Sullivan had been taking music composition lessons from Eric’s friend Harry Somers. Harry introduced Eric to Tim, and he introduced me to Eric. I was going into my third year at the University of Guelph as a Fine Art major.

My first meeting with Eric was with Timothy and my other two friends from high school, James A.J. Smith and Jim Carwana. His St. Jamestown (Toronto) apartment was cluttered, stuffy and could have used a good scrubbing. He offered us out of his meagre stocks a combination of Coke and beer, which he called “black velvet”. It wasn’t very good, but the conversation, as it often was with the four of us, was deep and intense. Eric loved it, but I remember him berating Jim Carwana for something, and as a result Jim did not return for later meetings.

I returned several times that summer, and exchanged almost a score of letters with Eric. One day, I was in Toronto and called him out of the blue. He answered, “Hello Michael.” Needless to say, in those days before caller id, I was nonplussed.

In one letter, I asked him if he could send me some biographical material. I had done a library search, and there was nothing available about Eric’s work. I thought that one day I might like to write something about him. He was flattered, and his reply was negative, but it was made with the skill and affection that is all Eric:

About me not telling you all, when Tim asked if he could bring you to meet me I did not dream that you expected me to boast of my accomplishments over the last fifty years. Sorry. Also I wilted when in your September letter you asked if I would give a condensed biography and memoirs for your and Tim’s benefit because you visualized my last breath at any moment. It is asking too much. I can give you just the latest “bits”… So… when you are older and I am amusing myself on a damp cloud strumming my little lyre you can do research all filed and ready to order.

Years later, I had forgotten about the question I asked, only to be reminded of it after I had started this project, when I found the only letter from him that I kept.

The book is in draft form with the NSCAD University Press and has expanded to include as a collaborator Brian Donnelly of Sheridan Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning. A new website, that includes some material omitted from the book, has just been launched at ericaldwinckle.info.

Last October, during my swing through China to promote NSCAD and our

Last October, during my swing through China to promote NSCAD and our