Today I perused the evaluations that my students submitted for last semester’s Introduction to Interactive Design course. Nobody’s perfect: some of the criticisms are valid. Often I’ll get one or two evaluations that say I’m the best, and one or two who say I’m the worst. This time was no exception, but I also noticed a number of instances of “we need handouts” in the comments section of the forms. Normally when I get five or six students saying the same thing, I take notice. But this time I thought: “Come on, you’ve got to be kidding me…”

The course is a basic boot camp for XHTML and CSS. It’s fairly straightforward and as long as the students tackle each weekly assignment, they will keep up. It isn’t rocket science, but students have to do the work, and for a 3-credit course, students are expected to spend around 6 hours out of class working on their assignments.

As time has gone by, I’ve noticed that the students’ expectations are changing. They are much more demanding, for one, and much less willing to accept that they need to work to find the answers to questions posed by the instructor. Whereas students a decade ago were willing to get their hands dirty, experimenting, discovering, and finding things out on their own, more and more students today are expecting us to give them the answers “on a silver platter.” Hey, Teach–you showed me, but I was up really late last night and I sort of dozed off in class so I didn’t take any notes. Can you give me a handout?

You want a handout? I’ll give you one better. I’ll let you in on a little secret: Google. Heard of it? It’s really cool…

If you forget how to add an image to your HTML page, try googling “image html” and you’ll see that there are 264 million results just waiting for you; ALL of the ones on the first page tell you how. Take your pick. If you forget about server side includes, try googling “server side includes” and you’ll get about a million results. And for the skeptical among you, I can assure you that all of the results on the first page are relevant matches for what you were asking for!

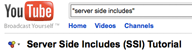

What? You say that you don’t like reading? [ sigh ] Ok, here’s another little secret: YouTube. Don’t tell anyone or you’ll spoil it. Search for “server side includes” in YouTube, and the top result is a 7-minute tutorial on server side includes.

What? You say that you don’t like reading? [ sigh ] Ok, here’s another little secret: YouTube. Don’t tell anyone or you’ll spoil it. Search for “server side includes” in YouTube, and the top result is a 7-minute tutorial on server side includes.

So please. Don’t ask for handouts. That’s so 1990’s.